The road to Hejira

Joni Mitchell's star-sailing, time-scrambling 1976 solo odyssey across America

In March 1976, Joni Mitchell packed up her car – a big boxy Mercedes 280SE she called Bluebird, bought with her first royalty cheque in 1969 – and headed out onto I-15, on her way to Damariscotta, Maine, about as far from Los Angeles as you could get while remaining in the continental USA. She didn’t have a driving licence but since when has that stopped her? She should have been promoting The Hissing Of Summer Lawns in Europe. Instead she was off on a wild goose chase across the country with an old lover and her latest flame, plus several trailers worth of emotional, psychological and pharmaceutical baggage.

She returned to LA a couple of months later, having clocked over 10,000 miles. She’d driven solo the length and breadth of the country, around the Gulf of Mexico, through the Deep South and the Sonoran Desert. She had assumed a variety of aliases and wigs. Her losses were plentiful: a fiancé (her drummer John Guerin), a shedload of money from the cancelled tour, much of her commercial momentum, her ego (for three days, after she encountered the rogue Buddhist guru, Chögyam Trungpa, in Boulder at the start of her trip), and apparently a full octave of her singing range. But she returned from her travels with rare and precious dream cargo: the nine songs that formed Hejira, her eighth and finest studio album.

It's possible to make a case for any of the albums recorded after 1970 as being the best Joni Mitchell album (and by implication, quite possibly the greatest album made by anyone, ever). But even Mitchell agreed. “A lot of people could have written a lot of my other songs,” she once confessed. “The songs on Hejira could only have come from me.”

Her previous albums had perfected genres. It’s hard to conceive of a greater confessional folk-rock album than Blue, a richer jazz-rock fusion than Court And Spark. Hejira seemed to mint new forms on every song. What do you call compositions like “Amelia”, “Refuge Of The Roads” or “Hejira” itself? Astral art song? Lunar blues? Desert ghost folk? As much as Low – composed over these same months an ocean and a continent away – Hejira is beyond old wave and new wave, a journey out of folk, jazz and rock into the wild blue aether, a strange frontier of the soul.

1976 was a Great Divide in the culture and many failed to make it across. Hejira was released a couple of weeks after Jimmy Carter was narrowly elected president, a couple of days before The Band played their farewell show at the Winterland. In the film of The Last Waltz, Robbie Robertson humblebragged his exhaustion to director Martin Scorsese. “The road was our school,” he sighed with a weary smile. “It taught us all we know. The road has taken a lot of great ones. Hank Williams. Buddy Holly. Otis Redding. Janis. Jimi Hendrix. Elvis. It’s a goddamn impossible way of life.”

For Mitchell, it was a second home. As she sang on one of her earliest songs, way back in 1966, she was “born to take the highway”. Hejira had begun life one year earlier, when she ran off to join the Rolling Thunder Revue, intrigued by the demos of Blood On The Tracks, flattered by the intimations of “Tangled Up in Blue”, but feeling that Dylan had betrayed his better instincts. She needed to talk to him, delve into his “silent mystery”. In the end she stayed just a month, long enough to dally with Sam Shepard and put Joan Baez’s nose out of joint.

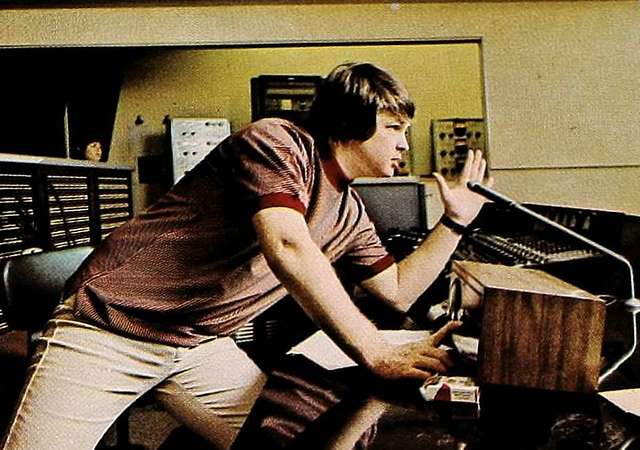

But she entered fully into the spirit of the mad escapade, insisting on being paid in cocaine, like circus clowns were paid in booze. Her own imperial wave was cresting. Just watch her in the Rolling Thunder footage, playing her work-in-progress “Coyote”, filmed at Gordon Lightfoot’s house in November.

She’s used to having all eyes on her (think of that photo of David Crosby and Eric Clapton, slackjawed in wonder as she plays in 1968), used to the musos following her left hand, trying to map her playing in conventional harmonic space. But now it’s Bob Dylan trying to keep up with her.

“Coyote” is the work of an artist at the peak of her powers, a writer whose senses have been sharpened by the thrill of the road, of racing and outpacing her peers. She’s supercharged by the first sweet rush of those fine white lines. It’s a delirious, infatuated fantasia of scrambled eggs and waitresses’ legs, burning farmhouses and air-conditioned cubicles, brood mares, appaloosas, eagles and tides.

You might imagine a whole album mining this rich vein, a raucous road movie, full of pills and powders and passion plays. But Hejira is the sound of a woman very deliberately running away from this particular circus. On the most basic, biographical level you might say it’s an album about fleeing romantic wreckage, or attempting to shake addiction. Or as she herself defined the word “hejira”: “running away with honour”. But at its most profound, Hejira is Joni Mitchell’s own declaration of independence.

The careering rhythms of “Coyote” find an echo on the second side, on “Black Crow” but now they’re rougher, the road is a rocky track rather than smooth interstate – it’s like the Rolling Thunder tour bus had taken a wrong turning and wound up in Death Valley. If the coyote is a worldly, charming trickster, at home in the motels and the whisker wheat, this crow is a wilder spirit animal, a ragged, scavenging soul, several rungs removed from human on Hejira’s totem pole. You hear this wildness in the playing of guitarist Larry Carlton, the jazz virtuoso shredding like a man possessed, his spangled lead lines now wailing and howling (Joni joked that she had to physically yank the sounds out of him).

You feel it most specifically in the gravity-defying swoops of bass prodigy Jaco Pastorius. Here at last was a player whose lust for freedom rivalled even her own. Pastorius famously pulled out the frets on his bass guitar because he felt they were speedbumps obstructing the ceaseless tumult of his music. With his playing, the verbal wildness of “Coyote” is sublimated into the very fabric of music. Hejira breaks the bounds of conventional musical gravity, ascends from the highway into the hexagram of the heavens.

After the rough and tumble of Rolling Thunder, in contrast to the Babylonian big band splendour of Court And Spark, Hejira has an eerie desert beauty, a dawning Georgia O’Keefe radiance. Mitchell, Carlton and Pastorius and are an uncanny, unearthly soft power trio. They never played together, never even met in the studio – the guitarist recorded in the daytime, while Pastorius overdubbed deep into the night, leaving Mitchell to tune and weave their strange frequencies together.

Like many a mystic, Mitchell finds illumination in desert visions. On the title track she and Pastorius ride out together, starsailing the solar winds into a cosmic wilderness beyond attachment, where we’re “only particles of change orbiting around the sun”. She finds a fellow traveller out in the bleak terrain of the burning desert, with Carlton’s guitar shimmering amid the vapour trails, in the ghost of Amelia Earhart, patron saint of solo voyagers.

No one, not even Earhart or Pastorius could survive at these icy altitudes for very long. And despite her three days of Zen in Boulder, Colorado, Joni’s ultimately too in love with the sensual world of Winn Dixie cold cuts, truck stops and crickets clicking in the ferns, too attuned to the slightest touch of stranger, to be a properly detached Buddhist for more than a moment.

But it’s part of her peculiar genius, the strange licence she does have, to be able to record what she hears up here, on these thin- air night flights and bring it all back down to earth, stow it in the trunk of her trusty Bluebird and take back to the reel-to-reels of the all night studios. It’s a song (as she sings on “Amelia”) “so wild and blue it scrambles time and seasons”. Maybe others could have written her earlier songs. But these songs? They could only have come from Joni Mitchell.