The freakiest show

In 2022, to mark the 50th anniversary of Ziggy Stardust, collaborators, historians, collectors and fans congregated in Liverpool for a weekend of communion, remembrance and celebration. Six years after his passing, David Bowie’s afterlife might turn out to be his most intriguing adventure of all…

Ziggy Stardust is alive and well and teetering up the steps of St George’s Hall in Liverpool. The old starman looks pretty good for 50: whip-thin in scarlet leather and platforms, crimson cockscomb proudly erect, the 1973 forehead flash the only odd anachronism. We follow him up the steps and into the madly ornate, neo-Grecian hall. Naturally, he has timed his entrance to perfection. The mirrorballs are twinkling, the crowd is expectant, and up in the loft the organist is playing Mick Ronson’s magnificent orchestral coda to “Life On Mars”.

But something’s awry. At the bar, there are three or four other Ziggys, patiently queuing for plastic beakers of Heineken. Around the hall, a rum selection of Thin (and not-so-thin) White Dukes. There are a couple of Major Toms, in spacesuits clearly not designed for sultry midsummer nights on Merseyside. There’s a dainty Pierrot queuing for the ladies, one terrifying New Romantic nun escaped from the “Ashes To Ashes” video, and a frankly sensational late-period Ziggy in light-up Kansai Yamamoto kabuki trousers. For one particular 10-year-old Duke it’s clearly all too much, and he’s led from the hall in tears by a paternal Aladdin Sane.

We are deep inside David Bowie’s multiverse of madness, and things are only getting stranger…

+++

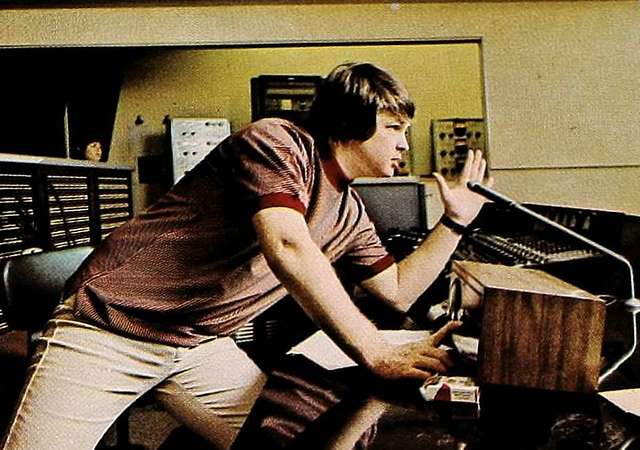

The Bowie Ball is the cracked cosplay centrepiece of the first ever David Bowie World Fan Convention, hosted by Dave Pichilingi of Liverpool Sound City and curated by Andy Jones and Nick Smart, co-editors of the David Bowie: Glamour fanzine. Over the course of a long weekend in mid-June, thousands of devoted Bowiephiles from across the world have descended upon Liverpool to hear from the man’s collaborators (Carlos Alomar, Robin Clark, Gail Ann Dorsey, Donny McCaslin, Woody Woodmansey, John Cambridge all hold court to packed, rapt audiences) biographers, photographers, designers and academics.

The convention is the most vivid instance yet of David Bowie’s miraculous afterlife, but throughout the summer of 2022, his continuing schedule puts the living to shame. Over the weekend, fans gossip about Brett Morgan’s forthcoming documentary Moonage Daydream. Worlds Inc – who created the first, now fetchingly quaint, online Bowie World in 1999 – announce the drop of their Bowie NFTs, part of a Bowie metaverse, “where augmented reality, cryptocurrencies, blockchain and non-fungible tokens have emerged as disruptive forces reshaping areas as diverse as music, gaming, sports, fine art collecting and shopping.”

Not to be outdone, Mattel reveals its second Bowie-themed Barbie doll; following 2019’s ‘Starman’ model, this is a ‘Life On Mars’ Ziggy, resplendent in powder-blue suit and mascara, though looking disconcertingly like Cilla Black. Hasbro have relaunched their Bowie edition Monopoly (“Invest in stages and stadiums and trade your way to rock ‘n’ roll success - but watch out for taxes, jail and bankruptcy!”). The BBC’s Great British Sewing Bee includes a ‘design a Bowie costume’ challenge, while the official Bowie Store is continuing its Bowie75 retail event, flogging, among other things, Scary Monsters-themed dog collars for your very own diamond dachshund.

Though the vessel of David Jones has perished, his ashes scattered to the breezes of Bali, the genie of David Bowie is set free to run wild across the culture. In the absence of any permanent resting place, no Graceland, Dollywood or Pere Lachaise for pilgrims to pay tribute, Bowie suddenly seems to be everything, everywhere, all at once.

If his career had been marked by astonishing, imperious artistic control, from killing off Ziggy onstage at Hammersmith at the height of his success, through to stage-managing the enigma of his own final curtain, now everything is up for grabs. Do you look for him in the corporate heavens of Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster, launched into orbit, eternally playing “Space Oddity”? Or in the industrial hell of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, where Bowie’s Phillip Jeffries has become incarnated as a kind of infernal tea kettle?

And is BowieCon simply a cosy exercise in nostalgia for retiring sixtysomethings, keen to recapture the fleeting intensity of their 1970s childhoods, and spend their savings on vintage satin and tat? Or an opportunity to explore the still evolving implications of an artist who feels like a vital beacon for 21st century genderqueer teens and drag artists?

+++

“Without sounding too wanky,” says Melissa, 60, an actor and lifelong fan from Lancashire, arriving at the convention on Friday afternoon, “it’s kind of a church.” Melissa entered the order when she was 14. “Young Americans was my way in. The Ziggy thing I was a little bit too young for. I used to look at him in Jackie magazine and be a bit scared.”

For her, “a lot of the appeal of the convention is just being with other fans. With there not being gigs any more, you really miss that community. When he died I was under a duvet for three days on the sofa, sobbing. My husband just kept bringing me cups of tea. It took a really long time to get over. For someone of my years it must sound a bit pathetic! I didn’t know the David Jones who sat in front of the TV in his underpants. I didn’t know the real man. What I fell in love with was what he chose for the world to see, I fell in love with what he was projecting. He inspired me to be my own boss, to make my own clothes. He had a massive influence. I feel like I’ve lost a friend…”

If Bowie is now a cult, it’s one with its own relics, holy scriptures and a burgeoning priesthood. As the convention marketplace sets up shop in Liverpool University’s student union, there’s a brisk trade in Bowie memorabilia and artwork: from dusty old clippings from 1960s newspapers to Maria Primolan’s eerie Raku ceramic busts of Bowie in every incarnation from The Man Who Sold The World to Blackstar’s Button Eyes, aligned like Futurama heads in jars.

“It’s interesting how the Bowie market has changed,” says Paul Wane, MD of Tracks Ltd, the UK’s leading music memorabilia dealers, who has a particularly keen view of the cultural marketplace. “When Freddie Mercury died, instantly everything went stratospheric, but then it fell again. With Bowie, when he died it gave the market a jolt, but since then it’s been a steady increase. It’s more solid now. Prior to his death some old things sold well, but now there’s interest in most things from throughout his career. But particularly the early 70s period.

“The most valuable items are clothing,” he continues. “For various shoots they’d hire costumes for the day. Currently we’ve got a boiler suit from the ‘Blue Jean’ video, a suit he wore in the film Absolute Beginners… I’d like to own some lyrics but they seem to be non-existent.”

Kevin Cann, one of the first and most meticulous Bowie chroniclers, has his own holy artefacts – notably the coffee table that once graced the Manchester Square living room where Bowie lived with his then-manager Ken Pitt in 1967. “It’s so special to me,” says Cann. “I had grown to be good friends with Ken from interviewing him over the years for my books. When he was moving from Manchester Square he said, ‘It’s yours.’ It’s a huge thing, it was actually made from a door. There’s a famous photo of David standing on the table from 1968, and of course, once I got it home I tried to stand on it myself. But it was so fragile I thought it would collapse. David must have been as light as a feather in those days!”

Nicholas Pegg’s exhaustive biography The Complete David Bowie, now in its seventh edition, has some claims to be one of the holy texts of the Bowie cult, though the man himself is more BBC sitcom vicar than cultish priest. “I would hesitate to suggest anything liturgical about my input,” he laughs. “People have been very kind about my book over the years. People do occasionally say it’s their Bowie bible and I’m very touched.

“I think if anything it’s increasing,” Pegg says of Bowie’s posthumous fandom. “It’s changed, of course. We know there won’t be any more new albums. In the wilderness years after the final tour, many people thought that was it. Of course he surprised us. But the interesting thing is that the commodification started in the noughties – you saw the Aladdin Sane, the Ziggy package start to crystallise. After The Next Day, after Blackstar, after David left us, it’s all opened out. One of the wonderful things is there are so many young people here who have only discovered him since he passed.

“Because his career was so prolific and varied and fecund and he had his fingers in so many different areas and cultural pies, there is still a world of potential and possibility and new ways of seeing and interpreting and revisiting DB. His importance in queer studies and gender studies is enormous – he’s a pioneer, practically the pioneer, especially for people of my age, growing up in the ’70s and ’80s. Seeing the video for ‘Boys Keep Swinging’ really meant a great deal to me. There weren’t other people putting that kind of stuff out there. In a funky, exciting, sexy way saying, ‘Whatever you are, that’s great, let me take you by the hand and let’s have an adventure…’”

At 25, Beth is one of the younger guests at BowieCon and her immaculately styled Thin White Duke hair sets her apart amid the grey and balding heads that dominate the weekend. “I properly discovered David when I was a teenager, seeing pictures of him from The Man Who Fell To Earth and thinking he looked like the most beautiful human being who ever lived. It was the imagery, but also hearing ‘Life On Mars?’ and thinking, why have I never delved into this? I became super-obsessed. It was weirdly the right time – I was 15 or 16, there was lots of identity, sexuality stuff going on. It was the perfect time to discover him.”

As an artist and animator, she’s inspired by Bowie the artist as much as Bowie the musician. “I love so much of his visualisation of his ideas, the costumes and the characters he came up with, the storytelling. I appreciate him as an entire artist. I was so upset when he died, but grateful that I could discover him when I needed him. I’ve been talking to older people here, saying we felt like we were born a generation late because we weren’t able to see him live and experience him as a person. For my generation who didn’t grow up with him onstage and see his development, he was more of an ethereal figure, a fantasy figure. It was all there for us to discover.”

+++

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies at Kingston University. In 2015, as part of an “immersive research project” for his academic study of Bowie, Forever Stardust, he spent a year “living as Bowie”: as far as possible visiting the same cities, reading the same books, wearing the same clothes and even eating the same food. He continues to follow the posthumous career with fascination, taking his students to visit the Brixton mural as a palimpsest of fan memory.

“One of my students last year had never heard of Bowie, which I think is a significant landmark event,” he says. “It will happen increasingly. He will pass out of history for a whole generation, perhaps. Meanwhile, we have Bowie as legacy property – Bowie as trophy object, competed over by those who knew him. Bowie as, interestingly, an unfamiliar, unknown figure to some young people. We also have Bowie as a ‘tame alien' – a safe sort of corporate mascot.”

Brooker acknowledges how Bowie still feels like an inspiration to gender-questioning teens. “Bowie as queer/trans ally is a current iteration, but I also suggest this is a retcon of sorts. To claim Bowie as a trans or queer ally is a re-reading in my opinion and involves putting a certain slant on the available evidence, constructing a specific meaning. We should also consider that some gay men felt very betrayed by Bowie in the 1980s when he claimed in Rolling Stone that his early-70s bisexual announcement had been a terrible mistake. Bowie was arguably quite appropriative of gay culture, and it could be said that he used it to provoke and to boost his own image. There is evidence that Angie in particular cynically and cannily pushed this image as she knew it would be good in the press.”

Nevertheless when we meet drag legend Auntie Climax (aka Liverpool artist Brendan Curtis-Brown) before the Bowie Ball, dolled up as a sinister glam clown wizard, a Bowie incarnation that never quite made it into this timeline, s/he is effusive. “I first discovered him via Labyrinth and I just thought, ‘Who is this wonderful creature?’ From there it was on to the music and the whole fabulous creation. When he died I cried more than my own granddad died. Which is a weird thing to admit, but it’s true. It affected me in a really visceral way.”

++++

BowieCon proves to be an intensely emotional experience all round. On stage, you’re never far from a group hug or a tearful standing ovation as Alomar and Clark talk about raising their family as Bowie’s New York neighbours, or when Woody Woodmansey remembers the early days when David persuaded the bluff, northern Spiders of the joys of stage makeup. Or when Donny McCaslin recalls the sheer liberty of working with Bowie in the studio, when John Cambridge recalls the in-jokes of a lifetime’s friendship, when Kevin Cann plays his own private interview footage of Ken Pitt, costumier Natasha Korniloff and Mick Ronson. It’s a timely reminder that for all the extraterrestrial glamour, the alienation and dramatic isolation of his art, Bowie was a funny, bewildering, daft human being, who for all his inspired talent also seemed to have a kind of transcendent gift for friendship and collaboration.

The back catalogue is playing non-stop through the weekend, songs that soundtracked and changed all our lives, songs we’ll never tire of hearing. But the tune that suddenly hits home as we sit in the coffeeshop watching the fans queue to have their pictures taken with a visibly touched Gail Ann Dorsey is “Everyone Says Hi”, that half-forgotten single from Heathen, supposedly written by Bowie in memory of his dad. The song pictures the afterlife as a kind of eerie, bleak cruise holiday with dodgy food. “I'd love to get a letter,” he sings wistfully, in the awkward way of English families, “Like to know what's what / Hope the weather's good and it's not too hot”.

BowieCon is full of these touching, gently surreal moments - stardust, art and mortality, folded into the texture of everyday lives. As Auden noted, writing of the Breughel painting that was one inspiration for The Man Who Fell to Earth, while Icarus falls from the sky, the ploughman, the sailors and the dogs, having seen something amazing, get on with their doggy days.

But some of those lives are changed subtly, profoundly, if undramatically, forever. On Saturday morning in a Beatles-themed city centre hotel, convention guests and celebs mingle at the breakfast buffet, waiting for their toast. Look, there’s Woody Woodmansey queuing for croissants; there’s Donny McCaslin getting his head around English hotel coffee. And there’s Jan and Lester from Solihull, reminiscing over the breakfast plates of a lifelong friendship founded on a shared obsession. They all encountered something incredible. They’re all still trying to make sense of it.