Suede: the insatiable ones

The mundane reality of addiction, it turns out, is not Byronic wraiths in Ghormenghast mansions but a pie-eyed Anderson plonking atonally on a cheap synth, vainly trying to compose Head Music.

Directed by Mike Christie

Release: November 2018

“The history of this fucking band is ridiculous,” said Brett Anderson, with exasperation and no little pride, way back in the late 20th century. “It's like Machiavelli rewriting Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. It involves a cast of thousands. It should star Charlton Heston . . . It's like a pram that's just been pushed down a hill. It's always been fiery and tempestuous and really on the edge and it never stops. I don't think it ever will."

He soberly alludes to the quote near the start of Mike Christie’s lurid, lairy, bittersweet take on the Suede story, first broadcast on SkyArts last year, now released on DVD. Somehow, contrary to all expectations, the infernal pram is still careering, with slightly more poise, through the 21st century, with a cast that includes Richard Osman and Ricky Gervais. How did this uniquely chaotic band, fuelled by a poisonous, hormonal cocktail of ambition, lust and revenge, somehow manage to reinvent themselves for chastened midlife?

Though it doesn’t shy from the squalor and the sleaze, Christie’s is very much the authorised, therapeutic, redemptive story. Drugs are a dark episode the band pulled through on the way to creative rebirth. Damon Albarn, such a pivotal figure in the early BritPop psychodrama, feels like the mockney elephant in the room as the cast recount the Suede origin story. And Bernard Butler, arguably the creative spark of the band is present only in old interviews.

But the film does benefit from access to Simon Gilbert’s vast personal video archive. A lot of this seems to consist of band members slumped in sundry studios and tourbuses, hungover, unshaven, smoking fags and flicking Vs at the handycam. But it also includes priceless early footage, from the nascent line-up still featuring Justine Frischmann, shambling through the Camden toilet-circuit years. It continues through to the the Spinal Tap fiasco of Bernard Butler's departure, with the band stuggling to compose their press statement, and the 17 year old Richard Oakes, blinking into the light for his audition as the replacement.

The most vivid footage however comes from the crash. Following the vindicative, vainglorious commercial success of Coming Up, and the endless international promotional tour, the singer retreated to Westbourne Park and pursued his crack habit with matchless, heedless gusto. No one has romanticised drugs as metaphor and lifestyle with as much guile as Anderson, and the sordid squalor displayed here feels like therapeutic atonement.

The mundane reality of addiction, it turns out, is not Byronic wraiths in Ghormenghast mansions, nor the airbrushed, neon bedsit fever-dreams of Peter Saville, but a pie-eyed Anderson, stained trackie bottoms hanging off his skinny arse, plonking atonally on a cheap synth, vainly trying to compose Head Music. “We knew if he came into the studio with his hair pushed back he’d been up all night smoking crack,” recalls Oakes ruefully. “If his hair was down we might get something out of him.”

What pulled them through? Following scenes where Anderson returns to the leafy suburbs of Haywards Heath, vainly looking for a hint of what spurred him on, and then tarries a while in the dark passageways and overpasses around Westbourne Park, the band emerge into well-groomed Bands Reunited middle age in the well-lit hall of the ICA, site of their 2003 farewell shows. It’s hard not to feel Anderson is staging an episode on his own personal twelve-step journey, apologising and making amends to the people he screwed over.

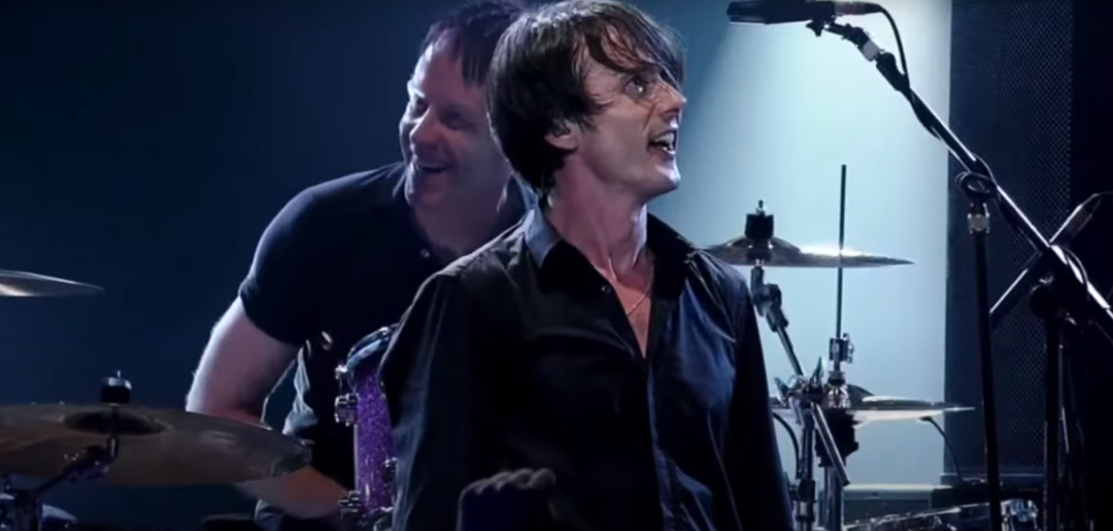

The creative rebirth of Suede remains mysterious: the crepuscular trilogy that reached a pinnacle with last year’s The Blue Hour is a genuine achievement that puts their peers to shame. And Coal Black Mornings, Anderson’s mordant memoir of scuffling through squats in search of success is one of the few rock biogs worth reading twice. You wonder if the real scandal of Suede’s insatiety isn’t pharmaceutical but rather showbiz: there’s nothing as addictive as the smell of the crowd, the roar of the greasepaint. In a film not short of altered states and chemical smiles, the look on Anderson’s face, onstage at the Albert Hall during the 2010 Teenage Cancer Trust comeback show, is perhaps the most hallucinatory of all.