Magic waves

Brian Wilson, 1942–2025

A couple of months after his death, it’s clear we are not done mourning Brian Wilson. At this point, no praise is too fulsome. To Bruce Springsteen he was “the visionary leader of America’s greatest band”. According to Van Dyke Parks “he moved mountains, he changed the language”. For Sean Ono Lennon he was “the American Mozart”. Randy Bachman added “He was Beethoven, he was Tchaikovsky.” As if that wasn’t enough, according to Al Jardine he was the man who “taught the world how to smile”.

You feel that for once The President has missed a trick. Pentagon Papers revealed a few years ago that Ronald Reagan personally intervened after the death of Dennis Wilson to ensure that the drummer received an unprecedented civilian burial in the Pacific Ocean back in 1984. Surely a real President would not have been satisfied with making a feeble social media post of condolence. A more proper presidential tribute would surely be to shoot Brian’s ashes into the 4th of July sky aboard a SpaceX rocket, sending him sailing serenely into the stars where no cloud or eclipse might ever darken his eternal sunshine.

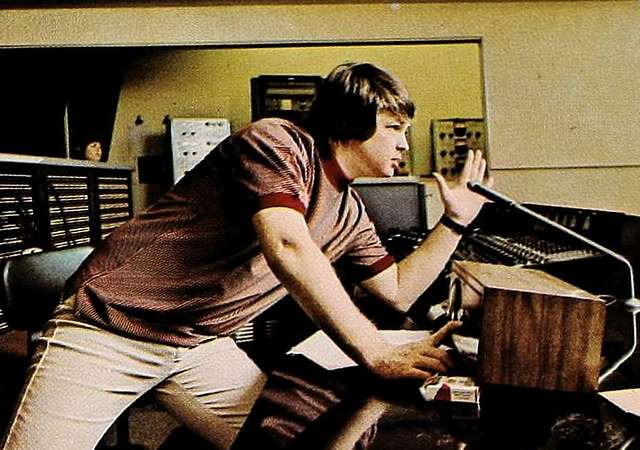

In truth it feels like we’ve been reckoning with the strange miracle of Brian Wilson for the better part of the 21st century, ever since that four night residency at the Royal Festival Hall in January 2002 where he played Pet Sounds in full, when dumb angels burst into song, grown men and women wept, and it felt like some great historical injustice had finally been redressed.

He was canonised in his own lifetime. The experience seemed to both console and bewilder him. After all this time, now that Pet Sounds has been fully and rhapsodically recognised, now that SMiLE has been painstakingly pieced together, now that even The Beach Boys Love You is getting its own box set, now that Brian is finally resting somewhere, somehow, in peace - do we have a clearer sense of his achievements?

A sober reassessment might raise some doubts. With a few exceptions - the influence of Chuck Berry and boogie woogie, jazz as refracted through the incandescent prism of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and a few songs on Disney soundtracks - the Beach Boys are the whitest major pop group this side of ABBA. “Psychedelic barbershop,” as Jimi Hendrix once joked. Can any act so eccentrically isolated from the major currents of 20th century music have a claim on being “America’s band”? What does it say about a country that its leaders repeatedly chose them for that role?

Does a songwriter who relied almost entirely on other people to come up with lyrics, and whose own contributions included “Hey Little Tomboy” (“No more skateboards, put away your baseball mitt / Your rough livin' days are through”), really count as someone who changed the language of popular song?

And does a musician who got an F from his high school music composition teacher and who was obsessed for long periods of his life with playing “Shortenin’ Bread” for hours at a time (one performance was so weird it caused Iggy Pop to flee the room in terror) qualify as an “American Mozart”?

But step away from the tributes, tune out the discourse, ignore the boxsets, the commemorative reissues, and allow yourself to be ambushed almost any sunny afternoon by “Heroes and Villains” soundtracking a farmyard escapade in Fantastic Mr Fox, or “Vegetables” somehow bubbling up from the depths of the algorithm and onto the car radio on a family roadtrip, even the opening bars of “Wouldn’t It Be Nice?”, somehow indestructible despite 50 years being press ganged into commercial praise of chocolate bars, washing powder and mobile phones, and you can be sent swooning once again by the casual brilliance of his music, as familiar as playground chants or folk song, as strange as angels.

Where did this magic come from? After all this time, are we any closer to accounting for it?

Just as Moses was forbidden from entering the Promised Land, it sometimes seems like the early settlers in California were cursed, incapable of appreciating the earthly paradise they had somehow stumbled into. For Bud Wilson and his fiercest son Murry, eventually finding their way from Kansas to Inglewood, Los Angeles in the early 1920s, the beach was a place where they once had to live in a tent. Both seemed scarred by what Joan Didion once called, with no little awe, “wagon-train morality” - that austere family loyalty that remained when “all the ephemera of civilisation [had] gone save that one vestigial taboo, the provision that no one should eat his own blood kin.”

They stopped short of that at least. But there was a brutality to the Wilson men, that only music could soothe. The young Murry soon realised that family singalongs were the surest way to bring the violence in his father under control, and in turn, the 14 year old Brian discovered that leading his brothers Dennis and Carl in an evening chorus of “Ivory Tower”, the Charms’ doo-wop cover of Cathy Carr’s 1956 hit, could bring their father to their bedroom door and to the brink of paternal affection.

It’s often insisted that Brian was the great laureate of ease, freedom and light: the whole white Californian promise of endless summer - and anything beyond that was just pretention and whining. It’s not just Mike Love who’s devoted to this immortal formula. In 1969, in Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, the first great elegy for rock and roll, Nik Cohn celebrated Brian’s “hymns of unlimited praise”, his authentic Pop Art invention of California, but scorned his lonely pursuit of masterpieces. By 1979 Greil Marcus wrote scathingly of “Brian Wilson’s thirteen-year failure to make a better record than “I Get Around”, and insisted there was more worth in “Be True to Your School” than “Surf’s Up”.

But what’s clear from an even cursory reading of the Brian Wilson biography is that he was motivated not by simple praise for sun, fun, surf and sand but by sheer unmitigated terror. He was hurt into song.

“I got scared into making good records,” he once said. “Being scared has probably been the most driving force that I have.” He was scared of Murry and scared of failure. Scared of girls and scared of flying. Scared of Phil Spector and scared of invisible vibrations that only animals can perceive. Scared of the power of his own music, and scared, ultimately, of the voices in his head, voices that had haunted him since his childhood, but which only became louder in his twenties, once dope and acid opened the doors of his mind and let all the angels and the demons in.

It feels too stupidly simple to find Brian’s primal wound in his almost entirely deaf right ear. For years he danced around the subject whether it was the result of one of his father’s beatings. Tom Nolan’s 1971 Rolling Stone feature concluded with a monstrous profile of Murry that despite his denials (“I never hit my kid on the ear. No. No. I was too strong.”) left you in little doubt.

But by the time of his second autobiography in 2016, Brian was insisting that, although Murry never stopped trying to beat the fear out of, or into, him, his deafness was actually caused by a neighbourhood kid lugging a lead pipe. Weirdly, Brian also recalled a story of his grandfather Buddy attacking Murry with a pipe of his own, leaving his father with his ear barely attached to his head. “Things repeat,” he wrote, mysteriously. “They repeat in strange ways.”

“Jesus that ear,” Bob Dylan once exclaimed. “He should donate it to the Smithsonian.” (An enormous Claes Oldenburg-style ear-shaped swimming pool might actually be a fitting monument.) In Bill Pohlad’s awkwardly touching biopic Love & Mercy (2014) the camera even attempts to journey, Fantastic Voyage-style, down that mythic auditory canal in search of the source of his genius.

It could be a Jack Kirby superhero origin story, some apocryphal, alternative version of Daredevil. A young nerd, smacked upside the head, finds himself tragically struck deaf in one ear. But the other is magically transformed, senses heightened and attuned to the MUSIC OF THE SPHERES. You can imagine the Kosmik Krackle with which Kirby might illustrate the sonic vibrations, hear the unearthly hymns our young hero might write for the Silver Surfer.

Maybe an artist like Jack Kirby - untrained, uncanny, somehow innately psychedelic, opening up strange portals and imbuing a pulp pop medium with more force than it could possible bear - might in fact be the closest parallel for Brian Wilson’s own peculiar genius.

There was strange magic at work in Los Angeles in the 1960s. Some say that the great magician of them all was Phil Spector.

He had the ghost of his own dad to contend with, and his own feelings of inadequacy and disgust. Above all he had a grandiose sense of revenge. From the summer of 1962, he began using the tiny Gold Star studio on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd and Vine as his own personal Manhattan Project, devising new ways to split the atoms of harmony and noise, exploding pop songs into cataclysmic two minute eruptions of lust, devotion and loss.

Up until the 1950s Hollywood had been the laboratory of industrial light and magic, where technicians engineered the celluloid dreams of the twentieth century. At Gold Star, the first real sound stage, Phil Spector founded the art of phonomancy, the casting of songs so powerful they could blow a hole in time and space. He constructed his records like Napoleon arranging his troops, like Wagner conjuring his valkyries. It was a military procedure, infernally plotted, with the patient accretion of platoons of guitars, bass, saxophones and drums, assembled until even “Zip a Dee Doo Dah” was an impregnable phalanx, intent on blowing away everything else on the airwaves.

The first time he heard the atomic sonic fusion of “Be My Baby” - how Spector melted the sound of the individual musicians down, and recast them into one titanic instrument - blew Brian Wilson’s beautiful mind. It made him feel like he’d been physically shot, right through the heart. He would play the single at home, face and chest pressed up close to the speakers, to be fully enveloped, as though he wanted to climb into the record and finally be safe, at home in his native soundworld.

Once the Beach Boys were signed to Capitol, Brian was determined to study Phil, understand how he cast these spells. He would lurk around Gold Star, get to know the musicians in the Wrecking Crew, learn how to assemble sounds into miraculous, impossible, five dimensional events.

At the same time he was burrowing into the Wall of Sound, figuring how to reconfigure and enchant it. Phil was determined to layer instruments until they were colossal, saturating the field of mono recording. Brian imagineered a kind of sonic fission. Instead of a cinemascope guitar, 10 times its natural size, how about some fabulous, chimerical new instrument - part guitar, part harp, part vibraphone, part sunflower, part Hal Blaine banging a plastic jug of Sparkletts spring water?

He wanted the expressive impact of the Spectorsound, married with the lucid space that Burt Bacharach had somehow divined in Manhattan’s Bell Sound Studio, all enchanted with his own flourishing, surreal sense of cosmic exotica. He wanted a sound that sparkled like California sunshine, both particle and wave…

When he recorded “Surfer Girl” in June 1963 at Western Studios, a short walk from Gold Star, Brian Wilson became maybe the first artist in history to produce a song that he had written and performed himself. It was a new kind of magic. In tribute to Hollywood’s founding sorcerer, the song was a shameless steal of “When You Wish Upon a Star” the national anthem of Disneyland. If early 1960s Los Angeles was a kind of enchanted Oz, then Brian became the good wizard of the west, sending out his spells onto the airwaves, counteracting the darkening vibes glowering ominously from the wicked wizard of the east.

From “Surfin Safari” through to “All Summer Long” the twenty tracks that were eventually compiled on Endless Summer are a yellow brick freeway away from Murry and out of Hawthorne, a miraculous conjuring of harmonies bold and bright enough to soothe all the voices that bickered inside Brian Wilson’s head.

But the Beatles, suddenly, miraculously, everywhere in 1964, suggested ways that fear and darkness could be acknowledged, brought into the music and maybe even tamed. If “Be My Baby” had been a single heart-stopping shot, then Rubber Soul, released in mangled but still stunning form in the US for Christmas 1965, was an immaculate barrage that love bombed Brian into surrender.

It was like the arrival of sound, colour and cinemascope in one twelve inch sleeve. He’d always wanted to create music you could swim into, get lost in. The kind of LP the Beatles were now making was a whole new playground for his burgeoning powers, a format at last commensurate with his capacity for musical wonder.

Though inspired by the Beatles, Pet Sounds was dedicated to Phil Spector - at once a tribute, and a demonstration of how thoroughly the apprentice had outgrown the sorcerer. It was the full flourishing and vindication of the lonesome auteur who recorded “Surfer Girl”, but the beginning of his isolation. His family were increasingly bewildered at the music he was creating. “Caroline No”, featuring just his voice, multitracked to mask his solitude , was released as a Brian Wilson solo single and failed to even reach the top 30. He was far out at sea on his own - maybe further than anyone had ever been.

He came back on the crest of “Good Vibrations”, the mightiest wave he ever caught. It was like Reed Richards discovering the portal into the Negative Zone, Mickey Mouse figuring out how to conduct the stars, planets and oceans. Conjured from his vexed feelings about Spector’s “You’ve Lost that Loving Feeling” and the Beatles’ Revolver, his dawning consciousness of the how waves and music and light were all limpid strings of cosmic vibration, thrilled at how this excited and terrified him even more than his father or Phil Spector, he conceived his grandest spell yet.

After 90 studio hours across seven months, using four studios and 30 musicians, and having spent $75,000, the stars aligned. Released in October 1966 “Good Vibrations” was an instant, irresistible worldwide smash - the most powerful, magical, mindblowing number one record the world has ever known.

If Brian’s story is a Marvel comics version of the sorcerer’s apprentice, then the SMiLE sessions are the moment when the magic goes wild, the sound turns untamed, the magician loses control. The songs he created through 1966 with Van Dyke Parkes chase the freight train at the close of Pet Sounds across centuries and through dimensions, rush out into the streets, starting fires on the streets of Los Angeles and in the mind of Charlie Manson. At one point in 1966 Thomas Pynchon made a visit to the Bellagio sandpit with his friend, Saturday Evening Post reporter Jules Siegel, and the experience surely fed into the serpentine, rhapsodic sentences of Gravity’s Rainbow and his imagining of the “soniferous aether”, the incredible, intolerable roaring of the sun we’ve all been taught not to hear.

It’s no slight on the Beach Boys later albums, or even’s Brian’s own frequently miraculous solo career to acknowledge that he could never catch that wave again. But then who did? After six decades of technological, pharmaceutical and financial proliferation - multitrack studios in the palm of your hand, digital surround sound, smart drug microdosing, artificial intelligence and the transformation of California into a private sandpit for a new generation of prodigal boy geniuses - there has never been a number one record to match “Good Vibrations”. It remains unsurpassed, a vibe that has never been shifted.

Thankfully, the smile, the wave, the magic Brian Wilson sent out into the universe eventually returned to him. It shows no sign of slowing down.