Fabulous beasts

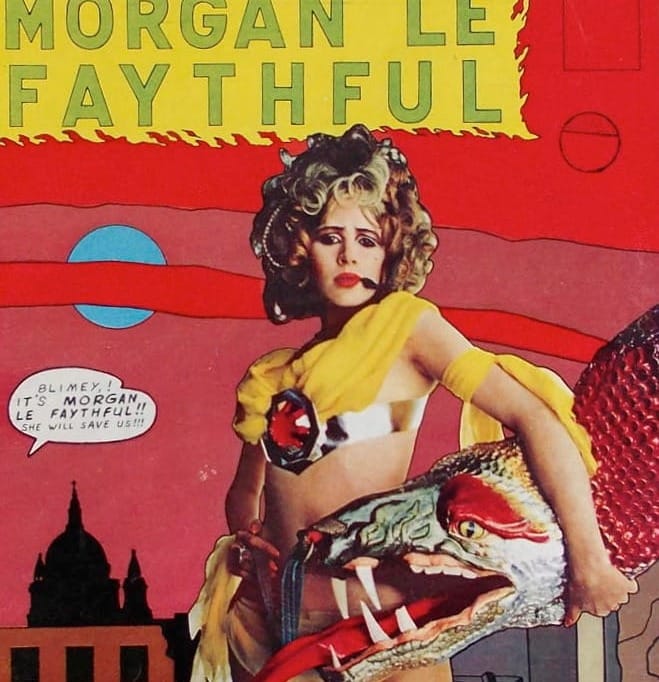

It dawned on Marianne Faithfull that she had a far grander destiny. To find the Holy Grail? To write the Modern Prometheus? Or to engineer a shift in western consciousness?

Marianne Faithfull 1946-2025

Though it’s a month since she passed, you can’t help but hope that Marianne Faithfull might yet reappear in a cloud of Gauloise, with an infernal dalmation in tow and some scandalously funny story about her latest season in hell.

She has form, after all. In Sydney, in the summer of 1969, she emerged from a six-day coma, induced by 150 sleeping pills, with tales of how she’d been chatting in some green room of the afterlife with the recently deceased Brian Jones (“Death is the next great adventure!” he told her, looking a little like the Mock Turtle from Alice in Wonderland).

And in Paris more recently, she returned from yet more comas with dreams of being transformed into a Romany blackbird, flying through 16th century England with Mab the Faerie Queen.

She enjoyed playing with the idea of her own myth, jousting with the “fabulous beast” of her legend, ever since her childhood, which she spent with one foot in fairytales and the other in the genteel poverty of 1950s Reading.

She’d been inducted into the realm of myth and legend by her mother, an honest-to-goodness Hapsburg Baroness, Weimar ballerina and the great niece of Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch. Her dad, Major Glynn Faithfull, had met the Baroness while working as British spy during the war, but was now a free-thinking utopian philosopher, intent on establishing a humanist commune in Oxfordshire. They were comically incompatible, and the marriage was short-lived.

It’s possible that Marianne Faithfull could have emerged from such a background intent on a quiet suburban life. But by the time she was a teenager, inexplicably educated at a private convent school, despite her family’s lack of either funds or faith, she was already intoxicated by philosophy, poetry and music, venturing far from Reading in search of magic.

She found it one Friday evening in March 1964, dragged by her Cambridge boyfriend to the launch party of Adrienne Posta’s “Shang A Doo Lang”, in the form of maverick pop impresario and Rolling Stones manager, Andrew Loog Oldham. For the myth-drunk Marianne, it’s like meeting the Mad Hatter, the Big Bad Wolf and Christopher Marlowe’s Mephistophilis, all in one devilishly seductive package.

+++

What did Andrew Loog Oldham see in the 17 year old convent girl? In his autobiography he says he caught sight of her and instantly recognised his world-historical duty. “In another century you’d have set sail for her,” he wrote, like a Spartan general embarking for Troy. “In 1964, you had to record her.” Marianne, in her own book, recalled a less lyrical motive: “He said, ‘I saw an angel with big tits and I signed her’.”

Her debut single is released just a couple of months later and goes straight into the top 10. As so often, Marianne was her own most astute critic. “As Tears Go By” was “The Lady of Shalott to the tune of “These Foolish Things" […] a marketable portrait of me and as such an extremely ingenious creation, a commercial fantasy that pushes all the right buttons."

Over the next three years she releases nine singles and three albums, tours relentlessly, shops heroically, smokes indefatigably, gets married to her Cambridge boyrfriend John Dunbar and has a son, Nicholas. It’s as though she’s on a mission to sample everything the world has to offer before she’s left her teens.

She’s amused by the spree, but even she makes no great claims for her pop career. She’s not as fierce as Lulu, as casual as Sandie or as imperious as Dusty. With a few notable exceptions (the singles “Come and Stay with Me” and “Go Away from My World”), her voice falls some way short of her dreams of Joan Baez. And, despite the prim audition recitals of Lewis Carroll and Shakespeare on her second album, her music rarely contains a glimmer of the darkling enchantment of her debut single.

If she had retired in 1965 after the birth of her son and settled down to dutiful adult life, it might be a pop career that only Morrissey remembered.

But by the summer of 1966, she’s already weary of playing the housewife. With her suitcase full of romantic literature, and a beautiful mind blossoming with every clumsily rolled joint, it’s dawning on her she has a far grander destiny. To find the Holy Grail? To write the Modern Prometheus? Or to engineer a shift in western consciousness? The trail she feels sure, must begin at the Gloucester Road apartment of Brian Jones and Anita Pallenberg.

+++

To the casual observer Marianne Faithfull spent the mid-sixties as Mick Jagger’s celebrity girlfriend and in truth she was only too happy give up the light entertainment treadmill. There were a couple of daft films (Girl on a Motorcycle might be most valuable for the photo of Marianne sandwiched between her co-star, the casually godlike Alain Delon, and Mick, looking more than ever like a shiftless student in odd socks), a few appearances on the stage (Irina in Three Sisters, Ophelia in Hamlet) and one more ornately folky album (1967’s Love in a Mist).

But mostly she retreated from the stage and retired to the vast king-sized bed that occupied the bedroom of her new home with Mick. Never mind a city, a street or a house, she could imagine that this bed, full of books, drugs, records, boys and girls, was the very epicentre of swinging London and she piloted it through the high sixties, like a magic carpet.

You can search fruitlessly for the Big Bang moment that started the 60s - Dylan plugging in, the Beatles turning on, Jimi touching down? But really, this has a good a claim as any of them. In most of these stories the women are background colour: the mini-skirted dollybirds on Ready Steady Go!, the shrieking crowd at Shea Stadium, the Sunset Strip groupies. And until fairly recently Anita Pallenberg and Marianne Faithfull were still portrayed as simply photogenic accessories, part of the rich supporting cast of The Rolling Stones Story, there for comfort, abuse and to inspire a deathless ballad or two.

But if there was what we now might call a vibe shift in London, and then across the world, through 1965-1967 then women like Anita and Marianne were just as much its engineers as Mick, Keith, John, Paul, Jimi, Brian and Syd. It’s they after all who had the social intelligence and ambassadorial guile to make the introductions and bring poets, musicians, film-makers, artists, dancers, designers together to flirt, fight, fuck and frolic. And it’s largely thanks to them that the moment had such style, intelligence, magic and, eventually, darkness.

+++

The magic carpet crash-landed abruptly in February 1967 when Marianne was part of the party busted by police at Redlands, Keith’s Sussex cottage. Things curdled catastrophically in the furore that followed the court case that summer, as Mick and Keith were prosecuted for possession and the identify of “Miss X”, the naked girl clad only in a fur rug, was drip-fed to the tabloids.

For Mick and Keith the whole sordid episode only burnished their myth, adding jailbird authenticity to their outlaw swagger. But for Marianne, beyond the petty vindictiveness of the prosecution, and the squalid invented details, straight from some cop’s dirty imagination, it felt like a kind of cosmic curse.

It was certainly a very public humiliation. In her mythic imagination, Marianne had been introduced into public life as the Lady of Shallot, a sad eyed princess, kidnapped by the pop machine. This was the moment, she later wrote, that she got into a boat, painted her name on it and drifted slowly downstream to the abyss.

The final years of 60s following the trial seemed to become a litany of doom: a miscarriage, the death of Brian, the beginning of addiction and eventually the overdose in Sydney, on her way to film Ned Kelly with Mick.

Perhaps most galling was the fate of “Sister Morphine”. She wrote the words in 1968 in a kind of trance, after growing tired of hearing Keith endlessly strumming the chords (“I realised that if someone didn’t write the lyrics, we’d be hearing this for the next ten years”), and the dark, unsettling power of the song was immediately obvious. It feels like a turning point, a third act that never happened, or was fatally postponed. She recorded the song with the Stones and Ry Cooder in LA 1968 as part of the Beggars Banquet sessions. It was released on Decca in February 1969. And after two days it was quietly withdrawn.

+++

If she had flirted with the idea of romantic damnation, her own season in hell now began in earnest. It lasted for most of the 1970s.

Like Dante, she plumbed several circles to really get a feel for the place. She started in Reading moving back in with her mum, who may have been in a worse state than she was. Suitors and would-be saviours came and went. An entire album, the wan Rich Kids Blues, was recorded with the ever faithful Mike Leander in 1971 (though it wasn’t released for another decade).

As if to confirm her abjection she accepted an offer from the occult director Kenneth Anger to appear as Lilith (Adam’s first wife, banished from the Garden of Eden for disobedience) in Lucifer Rising, filming in Egypt by the Sphinx and almost falling to her death in Germany.

She got it together in 1973 to perform “I Got You Babe” with David Bowie, wearing a nun’s habit (and not much more) for his 1980 Floor Show. Most surreal of all, she went country - or a kind of Marlene Dietrich idea of C&W - with Dreamin’ My Dreams, somehow managing to score a number one single in Ireland in 1976.

But the only place she really felt at home was a tumble-down bombsite wall in the middle of Soho where she would sit, numb with NHS heroin, and watch the whole mad parade go by.

In her own way way she was quietly inventing punk. Through dealers and band members, she eventually fell in Ben Brierly, lived with him in Chelsea squats, endured the scorn of Vivienne Westwood, and was briefly cast as Sid’s mum in the never-made Who Killed Bambi? But it wasn’t until 1979 that she could really make good on her discoveries.

She would refer to Broken English, the album she made in 1979 as “The Masterpiece” in her customary tone of mock grandiosity, daring you to take her seriously. It was certainly like nothing else in pop music. She sang, as Greil Marcus wrote at the time, “as if she means to get every needle, every junkie panic, every empty pill bottle and every filthy room into her voice”. And the music was something else: skewed reggae, oneiric synthpop, polished punk.

The centrepiece was “Why D'Ya Do It?”, the ferociously foul-mouthed ballad of erotic jealousy, written by the poet Heathcote Williams supposedly with Tina Turner in mind, but swiftly seized upon by Marianne as her “Frankenstein” at last, her equivalent of the masterpiece that Mary Shelley pulled out one weekend amid all those damned poets. In Australia her label refused to release it. 10 years too late maybe, but here at last was the sequel that “Sister Morphine” deserved.

+++

Naturally the sudden rise to acclaim, success and cashflow after so long in the wilderness came at a price, and the relapse into addiction was savage. But by 1987 she was close to clean, and recording Strange Weather, an album of artful blues, featuring songs by Tom Waits, Dylan, Leadbelly, expertly curated by Hal Wilner.

It marked the beginning of an unexpectedly extensive victory lap, taking in Brechtian cabaret (Seven Deadly Sins, 1988), contemporary tributes (notably 2002’s Kissin Time, featuring Beck, Blur and Billy Corgan, among many others) and conceptual covers (Easy Come, Easy Go, featuring her version of songs by Morrissey, Dolly Parton and Espers being the pick).

Just as she’d once felt like she’d been adopted by Anita Pallenberg and Brian Jones back in the mid-60s, in the noughties it felt like she’d found some kind of gothic surrogate family with Nick Cave, Warren Ellis and PJ Harvey, who worked together in 2004 on Before the Poison.

In 2021, working again with Cave and Ellis, she fulfilled a lifetime ambition, recording She Walks in Beauty, sublime settings of beloved poems by Byron, Keats and Shelley. Naturally it concluded with Tennyson’s Lady of Shallot, the poem that lay somewhere behind her debut single from 60 years ago:

It was the closing of the day

She loos’d the chain and down she lay

The broad stream bore her faraway.